Italia 70 - The Sound of Political Dissent / Bologna - Liscio Dancehalls as Socialist Resistance Against Disco’s Liberalism

When in August 1980 Bologna is hit by a devastating terror attack, the city is stuck between the old-fashioned folklorist tradition of Liscio and the roaring rise of Italo Disco under the influence of American liberalism. Meanwhile, heroin and punk creep through a scarred city.

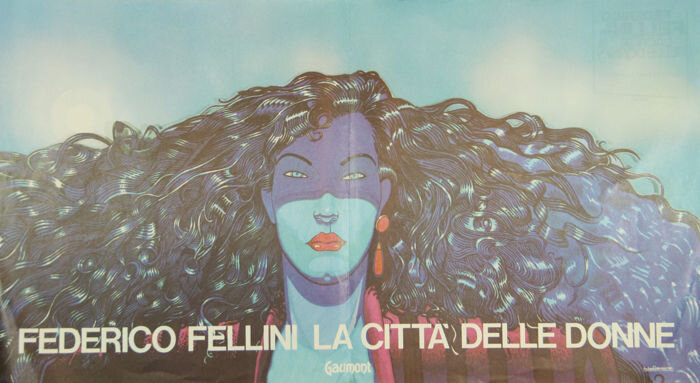

A woman is walking under the scorching sun of August in a small town near Bologna, Italy. She swings by a huge poster illustrated by a renowned artist called Andrea Pazienza - it is the poster for the movie City of Women by Federico Fellini. The movie has just been exhibited at the 33rd International Venice Film Festival and describes the journey of Snàporaz, a man who is trying to find himself and understand the female species - all displayed in Fellini-esque dream-like fashion.

The lady opens a big iron door. A light is shed over a wide dancing ballroom, that in this part of Italy is called Balera. She is a 50-year-old and she is wearing flower-patterned apparel, one of those that housewives buy for five thousand Lire at the local market. The dress is a bit tight, but it is fresh and light, perfect for these hot August days. The Balera is still untidy from the night before: glasses on tables, cigarette butts on the floor, and that sweet smell of wine and sweaty bodies in the air.

She has to clean the Balera before the owner comes back from Bologna, with the 10.30 am train. The orchestra Spettacolo played the night before until very late, that mix of Polka, Mazurka, Cha-Cha, and Valzer that in Italy goes by the name of Liscio. Once the soundtrack of the lower-middle-class - common people with ordinary jobs - Liscio has been evolving during the 20th century, becoming music for retired elders. Old gentlemen in tuxedos falling in love with smart widows under the sound of a glittered red jacket-wearing band with two singers, a brass and a rhythm section, and the quintessential accordion.

Federico Fellini kept his 1980 film City of Women an Emilia Romagna affair when he picked Bolognese maverick comic drawer Andrea Pazienza to illustrate the movie’s poster.

Just like in a postcard, that Saturday morning, everything seems perfect: the bright blue light of the sky, the warm wind of the summer, and brightened beaches look as if they have been painted on a canvas, especially in Emilia, the region she lives in. For the last few years, hordes of tourists coming from the north of Europe have been descending to Italy to listen to the sound of what the Dutch have unashamedly named “Italo Disco”. From Milan to Rome, via Rimini and Riccione, several clubs and discotheques have opened over the last years. Clubs like Altro Mondo Studio or Easy Going, have become the core of that sound that is driving Europeans mad: robotic music made out Roland keyboards, played by a DJ instead of a real band.

A new generation of Italians inaugurated the 80s, the Plastic Years par excellence. A decade made of fashion and advertising, the arena for social change where entrepreneur and soon-to-become politician Silvio Berlusconi is finding his space out of the repetitive beats of Italo Disco. Songs with made-up English lyrics, often without any meaning, are becoming hymns for the generation of the hedonistic youth, a generation in need of escapism from the tough 70s. During these years, while discotheques increase their popularity, Baleres are trudging, albeit still shelters for former Partigiani and elders in love.

Until the 1980s, in Bologna and the whole of Emilia Romagna Liscio orchestras were more popular than rockstars.

The woman switches on a little light blue Brondi tv set, left on top of the counter by the till, and lazily turns to the coffee machine to fix herself an espresso. She likes to watch Canale 5, the newborn tv channel owned by businessman Silvio Berlusconi. She particularly enjoys Dallas, a soap opera from Texas: she fancies those ambitious characters, although she does not approve of their lavish and arrogant lifestyle. The woman cleans the ballroom with precision - she has been doing this for years since she is paying for her daughter’s studies at DAMS - the art college in Bologna.

The job at the Balera is easy and makes her happy, that festive mood of the environment represents some sort of comfort to her. To make things easier, it is close to her home and it is located in a very small satellite village near Bologna. The town was safer a few years before, now it is full of heroin junkies, or as they call them in that part of Italy “Bucomani” (addicted to holes). Together with a more liberal attitude towards business, the 80s are bringing also a lot of heroin, replacing more hippie drugs such as weed and LSD.

At college, her daughter is involved in the independent broadcaster Radio Alice, produced by the pupils of philosopher Umberto Eco and intellectual, translator, and writer Gianni Celati. They play the popular Disco Music and contemporary rock acts, such as the youth idol Vasco Rossi and his outrageous song 'Fegato, Fegato Spappolato' (Liver, Destroyed Liver) featured in his latest album, provokingly titled Non Siamo Mica Gli Americani (We Ain't Americans). Sadly, they seem to have forgotten her mother's beloved Liscio, especially that of Secondo Casadei, violinist, and Liscio superstar.

Still from Vasco Rossi’s ‘Fegato, Fegato Spappolato’ promo video. At the turn of the decade, Rossi’s lazy blend of rock, reggae and disco and his outrageous lyrics become a symbol and a lifestyle for many Italian teenagers willing to break free from the political violence of the 70s.

The American ethos winds persistently around the life of the Italians in the 80s. From fashion to politics, from food to Disco Music, the Americans are imposing their capitalistic way of life, gaining many followers among the young Italians, tired of a decade, the 70s, overly politicised and painfully violent. In music, this economical account, is shown throughout Disco, which well matches the Italian sense of melody. Among a plethora of others, Capricorn, Kasso and Gepy & Gepy are producing several brilliant Disco tunes in Rome, while Milan - with La Bionda brothers and their side-project D.D. Sound - is scoring the soundtrack of the infamous hedonistic Yuppy-oriented “Milano Da Bere” (a slogan coined by the renowned copywriter Marco Mignani for the Amaro Ramazzotti adverts and that could be translated as “Swinging Milan” ).

Bologna, via New York, is gaining international recognition because of the genius of Mauro Malavasi, author of hundreds of classics both as producer and writer, and because of Celso Valli, capable hitmaker of modern Disco tunes such as ‘Self Emotion’ and many more. When it comes to music, Italy is finally breathing. Disco definitely represents the much-needed fresh air after a decade of progressive rock bands and politicised chanson troubadours. Italo Disco quickly becomes the way teenagers express their disappointment towards the dark 70s: they desperately need escapism from political violence, they desperately need to embrace a new lifestyle. What’s better than discotheques, then?

Between the 70s and the 80s Emilia Romagna, with its sandy riviera and multitude of discotheques, became the hotbed of Italo Disco.

At the time of our story, Italy is tired and scarred after continued terrorist attacks by both far-right and left extra-parliamentary groups. In 1977 the Red Brigades kidnapped and killed the Christian Democrats leader and statesman Aldo Moro, and since then they have been preserving their strategy of terror; kneecapping, murdering and kidnapping politicians, bankers, judges, magistrates, prosecutors, journalists, and cops.

If this wasn’t enough, on June 27th, 1980, a plane flying from Bologna to Palermo mysteriously fell into the Mediterranean Sea, killing a total of 81 people. The Ustica Massacre, as it is called, still does not have its causes legally confirmed, albeit it is commonly accepted that might have happened because of a mistake from France and NATO. Their real target was the Libyan dictator Muammar Gheddafi, who was flying to Poland across a similar route, shadowed underneath the Italian DC-9 aircraft. At the time, it was common practice for the dictator to fly hidden from NATO radars with the complicity of the Italian government.

The news of the still unsolved Ustica Massacre shook the Italian population in the summer of 1980.

Although this could sound strange, Gheddafi and his country have had a very important role in the history of Italy during the 70s, because of the interest from the government in the Northern African oil and because of the pro-Palestine and pro-Libya pacts statesman Aldo Moro made over the years.

Bologna, more than any other Italian city, canalizes the panic, horror, and tension of the political dissent of these years, becoming the symbol of a rotten, heroin-addicted, and hopeless country in the pages of the superb comic Penthotal by Andrea Pazienza, the most genuine representation of the desperation of the disenchanted country Italy had become.

Bands like Gaznevada (a conceptual and stylistic melting pot of these years) and labels like Harpo’s Music managed to put into music this hanger and frustration. Musicians, cultural agitators, and intellectuals gravitate around Bologna art college, making it an international pole for artists. The soundtrack of the dissent in Bologna is punk, pissed-off, and full of heroin.

Gaznevada, with their mix of Punk, New Wave and Italo Disco, are among the most peculiar acts of the burgeoning Bolognese Punk scene.

Canale 5's Fininvest promotions are loud and annoying, distinctively different in their style and ethos from the old-school RAI TV Carosello adverts for Barilla pasta. Now, they even broadcast infomercials: long videos of people selling to housewives a set of pots and vessels, all easily payable over monthly installments. The woman does not like this intrusion of privacy, it is too cheap; she mutes the television set and switches onto Radio Zeta, 24/7 of Liscio music.

While mopping the floor, she listens to the Mazurka by Raoul Casadei, the young heir of the Casadei dynasty - over the years he has reinvented Liscio music, speeding it up and putting the accordion from Stradella at the center of the orchestra. The sound of clarinet leads the woman to her past: she is young again and she is with her husband Antonio, in that very same Balera. They were happy, and he was alive; her waist was so thin.

She is wondering if these kids in discotheques still fall in love, and if they do, how can they with that electronic music? Among all those lasers and smoke? Do they fall in love over that plastic world? She holds the mop and balls with it, like it’s Antonio, while Raoul Casadei sings: “Beauty, a flower in the hair, I wonder if I am living a dream, beauty, beauty, I seek for you and you don’t know it, baby your image is in my soul”. She moves on the dancefloor, the music is loud and she cries, there’s no more Antonio, her daughter never comes home, a broom is all that’s left in her hands. The muted TV stops broadcasting Dallas.

Balere like Ravenna Casa del Liscio (Liscio Home) were massive dancehalls where a transversal, mostly lower-middle-class and working-class audience gathered on weekends to dance to local folk music.

BREAKING NEWS appears on the screen in a primitive electronic font. Footage of a bombing, smoke, a lot of smoke, people screaming, in the background the music of 'La Mazurka di Periferia' by Raoul Casadei plays. A broken clock resembles the one in Bologna central station, but it cannot be Bologna, it can’t be… we are not the Americans, we don’t throw bombs. It can’t be…

At 10.25 am on the August 2nd, 1980, a bomb detonates at the train station of Bologna. The city is in turmoil, confused journalists are running to the station, ambulances and firefighters, bus number 37 loading bodies instead of passengers, the army, the police: everybody is trying to save as many lives as possible, under an ocean of broken bricks and glasses. This is war.

When newscasts’ cameras reach Bologna train station the images reaching the homes of Italians are of pure devastation.

These crystal neat images will be impressed into the Italian collective imagery for the years to come: a broken clock with its hands stopped, perhaps trying to freeze the memory of the 85 deaths and 200 injured. Over the years, several theories on the bombing attack: the Neo-Fascists (who have been bombing trains and stations for the whole of the 70s), or maybe the Red Brigades. They have been killing many people, although bombing was not their medium.

According to a different theory, it was Gheddafi and the Libyan secret services, upset with the Italian government for the Ustica Massacre - someone must have said to NATO about Gheddafi's habit of secretly flying over the Italian Peninsula.

Our lady watches the TV, the mop is at her feet, the Liscio plays very emphatically, she can’t understand, she just hopes her daughter is not there. Antonio is dead, she can't lose her daughter too.

The train station’s clock, shattered into pieces and stuck on 10.25 am, is the symbol of the Bologna Massacre.

The Ustica and the Bologna Massacre reach the benchmark of violence in Italy. A cold war scenario for the dominance of the Mediterranean area, with big players around the table of international politics, was played in Italy. The players were Europe, USSR, the USA, Palestine, Israel, and Libya, all influencing Italian politics and all influenced by the Italian politicians: by the Masonic lodge P2, by Christian Democrats such as Andreotti, and by Aldo Moro himself.

Neo-Fascist groups, far-left parties, proletariat groups, the strategy of tension, and several false leads made 1980 an intricate year, turning Italy into the most violent place in Europe. The socialist dream was coming to an end, replaced by neo-liberal philosophies imposed by Margaret Thatcher and Jimmy Carter.

One of the key symbols of vanishing socialism, Balere dancehalls, were plodding, crushed underneath the burgeoning hype of discotheques and clubs. Their music - East European-influenced Polka and Mazurka, or South American Cha Cha and Mambo -was replaced by American Disco. The 80s started with a bombing and its scar is still hurting the country to these days.