Fashion and Advertising Photography in 1970s and 80s Italy - Franco Turcati

Franco Turcati turned a passion for photography into a career in advertising thanks to his savoir faire and a strong, authentic artistic vision. We reached him in his archive in Turin to discuss the tricks of his trade, secretly turning into a paparazzi to shoot Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull’s love getaway, and contributing to establish Superga as a worldwide brand.

Where to start with Franco Turcati? It is no easy job to pin point the life of a creative who went from shooting still semi-unknown Italian pop stars to exporting Italian fashion worldwide. Turcati’s story, in fact, is not just a matter of a conventional career, but one where private and professional life intertwine and are mutually responsible for making him one of the most celebrated photographers in Italian advertising.

“I was a war orphan. I spent seven years in an institute-cum-graphic school run by priests. We’d have our group photos taken every now and then, that’s when I started showing an interest towards photography.” One can tell from the start that Turcati’s story is different from that of many other photographers. His life, in fact, seemed to have taken him on a different path from the start.

“After completing my graphic design studies, I moved to Turin but to pay the bills I soon started working as a vendor. I spent three years at [chocolate company] Perugina, prior to that I would sell typewriters door to door for six months. At Perugina, though, they had an American company training employees on interpersonal relationships and trading techniques,” reminisces Turcati, “That turned me into a great seller, despite I didn’t manage to sell my photos well in the years to come [laughs].”

Above: model Bibi shot by Franco Turcati. / Top right: (Clockwise) Visual artist Enrico Colombotto Rosso, painter Mario Molinari, and hairdresser Salvatore Giacco shot for L’Uomo Vogue cover. Franco Turcati

However, those communication skills stayed with Franco when he quit his job and nearly unconsciously dived into photography as a freelancer. “When I left Perugina and decided I wanted to become a photographer I taught the techniques myself by reading the few magazines available back then. No one was really teaching anything. It was seen as a darkroom secret.”

Despite the majority of Italian media was based in Milano, Franco started developing good relationships with a Torinese firm that printed established automobile magazine Quattroruote, that launched Turcati’s career in photography first and then in advertising.

“When I was 25, I dared and walked into the Quattroruote offices to hand in some photos. They liked them and me, so they started to hire me for photoshoots,” explains Turcati.

Within the same building where Quattroruote magazine was print there was another office, the headquarters of Radio Corriere Rai, a weekly publication backed by the Italian public service broadcaster RAI. “There I befriended some journalists, so I started shooting for them too as a freelance. It was mostly pop singers. I used the excuse I was working for the Radio Corriere Rai to shoot these artists, but I would actually try to sell the photos to a publisher in Milano that printed music magazines for teenagers. I sold many photographs, but they never paid me!”

Franco’s charm and buoyant mood helped him to instantly establish a connection with musicians which resulted in intimate shots that one would expect from a tour photographer or a long-time friend. The photos of a yet semi-known Lucio Dalla with his band Gli Idoli not only capture the photographer’s talent but also his ability to establish a unique feeling of confidence with his subjects.

Equipe 84, I Nomadi, Little Stevie Wonder, Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull are just some of the pop stars Turcati befriended and shot in the late 1960s. Franco Turcati.

During these times, in the same offices, Franco met Geoffrey Parkin, a British journalist who worked as a correspondent for many British newspapers. “One day he informed me that rumours were circulating about Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull being on a love getaway in [Italian seaside town] Sanremo, because Marianne was taking part to the city’s music festival. I papped them at the Grand Hotel del Mare in Bordighera, nearby Sanremo, having breakfast” remembers Franco smiling. In those very same hectic days during the festival Franco roams the Sanremese night attending crazy afterparties, even bumping into a young Stevie Wonder drumming like crazy on Italian beat group Ribelli’s kit. The writing ‘cocaina’ - which doesn’t require of any translation – on the drum just below the band’s name tells loads about the atmosphere of those psyched-out years.

Another of Parkin’s tip-offs led Turcati to meet Michael Caine and shoot the cast of The Italian Job while working on the film in the city in 1968. Those are years of frenetic work, from fashion shootings to nightlife ones. “In 1970 I spent three nights as the only photographer shooting Mina’s residency [picture an Italian version of Dusty Springfield-meets-Shirley Bassey] at Mack 1 club. I was the first photographer to ever understand that she was performing with her hands. Most people would focus on her face, but I didn’t. She was enthusiastic of me discovering that.”

A series capturing Mina and her expressive use of hands at Mac Uno, Turin, 1970. Franco Turcati

Although these jobs were Turcati’s bread and butter, it was his collaboration with Quattroruote that turned into a springboard for a career in advertising at the turn of the 70s.

Franco, in fact, was used to shoot Alfa Romeo automobiles for the Turin-based car dealership Monzeglio, that in the early 70s became the first Italian importer of Suzuki motorbikes. “This gentleman called Hideyuki Miyakawa, who had come to Italy all the way from Japan on a motorbike. He married Maria Luisa Bassano, a woman from Turin, and started working as a middle man between Monzeglio and Suzuki. He was an extremely talented guy who soon turned into a close collaborator of [esteemed Italian car designer] Giugiaro, becoming his right-arm in the world.”

In 1965, quipped with a Nikon F with a 300mm telephoto lens lent to him by Quattroruote, Franco dived into advertising by shooting the first iconic Suzuki Italian campaigns. The sensual ‘Io Suzuki e Tu?’ campaign paired motorbikes and girls with the typical male gaze of those days, but it was also a fantastic insight into the transitioning phase of late 60s and early 70s female fashion. Modelled by Turcati’s teenage friend and model Lia Dezman, the adverts featured curly wigs, knee-high vinyl boots, and see-through crochet garments. However, to shock the public opinion was the following campaign. With a slogan conceived by ad woman Vilma Cino and inspired by a quote from George Orwell’s Animal Farm, the campaign titled ‘Donne e moto sono tutte uguali, ma qualcuna è più uguale’ (‘All women and bikes are equal, but some are more equal than others.’)

The Suzuki ad campaigns photographs that scandalised a whole country. Franco Turcati.

“It was the first ad campaign to be condemned in Italy by the Istituto di Autodisciplina Pubblictaria, a newly formed body that sanctioned offensive adverts,” explains Turcati. “Despite Vilma was a woman herself and was inspired by Orwell, the advert was accused of sexism. Back then, the fire of feminism was just starting in Italy and, at the same time, [photographer] Oliviero Toscani’s bum for the Jesus Jeans advertising campaign had just come out too. Both adverts were targeted by Angelo Pezzana, the founder of FUORI the first Italian gay movement, who at night time would cover the billboards with massive stickers saying ‘this advert offends women.’ The fun fact is that some years later I met Pezzana, whilst on holiday in Sicily, and he proudly told me the anecdote. Those were very peculiar and amusing times,” giggles Turcati.

As a consequence, Suzuki had to change its advertising strategy and came up with the ‘Suzuki Isola D’Acciaio’ (Suzuki Steel Island) slogan. The campaign, shot on the Forte dei Marmi beach, despite its futuristic appeal didn’t reach the same level of popularity of the previous incriminated one. In the company’s Japanese headquarters, a decision was taken to opt for more sober campaigns.

“The Japanese didn’t like the campaign condemnation despite it brought lots of attention to the brand against much stronger competitors like Honda, Kawasaki, Laverda, and Guzzi. They signed a deal with a new advertising firm, OPIT from Milan and booked the Monza circuit to shoot a campaign there. I regretfully have to say that it was insignificant. When the agency accepts a compromise with the client, creativity is lost.”

Denny Hulme and Graham Hill at 1969 Monaco GP, where Franco had to be like a bullfigther to capture the cars’ dynamic movement. Franco Turcati.

Creativity, but also a clever use of colours, is what made early 1970s motorbike campaigns special, thinks Turcati, who sees in those times the peak of advertising. “The majority of other brands’ adverts, including Piaggio despite its decent communication strategy, featured photos that weren’t captivating. The photograph is always the first thing you read, the caption comes later.

“After we were the first to try different and challenging campaigns out, most motorbike adverts turned extremely vulgar and tasteless. The copy and paste generation of the Macintosh era overall ruined the style,” observes Turcati, “With the advent of computers we were enthusiastic at first, but then I realised that the market suddenly changed, opening to a multitude of young people who haven’t got any true grasp of typography and design. There has been a fall in our interlocutors. We were used to grow professionally by confronting ourselves with great entrepreneurs and art directors.”

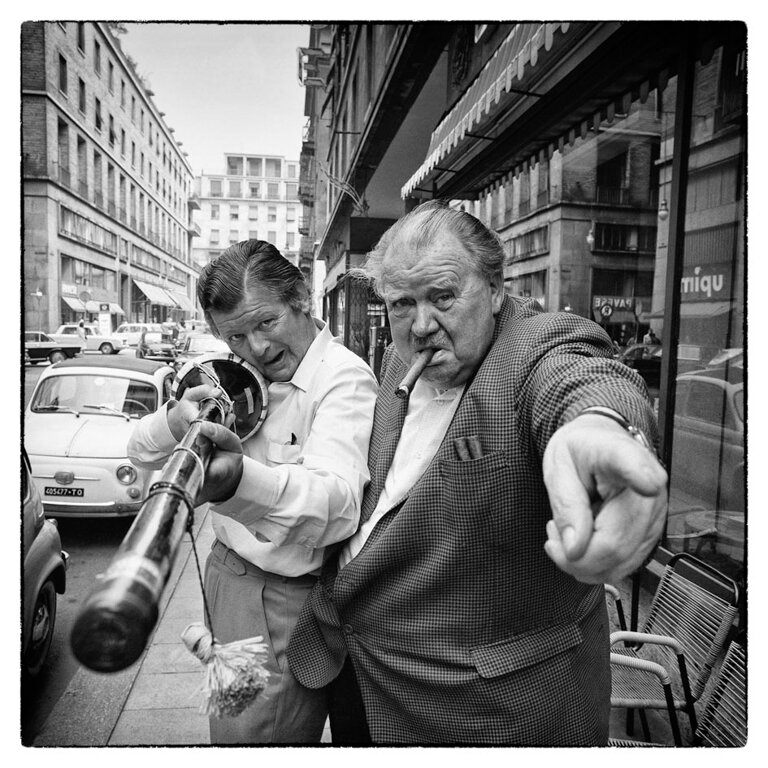

Above: British actors Benny Hill and Fred Emney point a bottle of Chianti to Turcati’s camera outside their Turin hotel during a break from the filming of The Italian Job. / Top Right: Michael Caine and his then girlfriend Bianca Jagger enjoying a drink in a Turin nightclub.

Franco’s words make even more sense in the light of his past at Mark 3 magazine, a publication that made graphic design the core of its editorial line. There, in 1967, Turcati worked under the direction of Danilo Nubioli, the acclaimed designer responsible for the Italia ‘61 graphics. “He took the Helvetica Bold font, cut it letter by letter and stuck them together to create a fresh take on the font. One time, when he designed the [ball bearing firm] SKF stand for the Salone della Tecnica it didn’t even look like a stand, it was a sculpture, shaped in the style of a ball, all in white,” reminisces Turcati, “Danilo was a character with a fantastic energy who would inspire me loads.”

Being a freelancer, though, always pushed Turcati to go forward, growing professionally and never settling for what he had. “If I had been hired, I would have probably stopped to experiment,” says Franco. It was this attitude alongside the experience gathered so far that, by the early 1980s, brought him to go solo first and then progressively set up an advertising and communication company of his own. Here, although his job remained the same, the attitude to it changed.

“I would consider myself the striker, but behind me there was a team. My wife, who had remarkable skills, curated the styling together with an art director who would select the models, because I lacked of that sensibility,” explains Turcati.

Securing K-Way and Superga communication strategies, Turcati had therefore the opportunity to start a decade of intense activity in the fashion industry. Nailing the two brands’ first campaigns Turcati’s studio played an essential role in exporting Italian fashion abroad.

Neoclassical and tennis aesthetics inspired Turcati’s Superga campaigns shot in Rome, Ancona and Beaulieu in 1987 and 1988. Franco Turcati

“We reinvented the way tennis sneakers were seen. In the mid-80s they were intended as a cheap product, but by the time we took their communication strategy over most brands at the Milan Fashion Week, between 1985 and 1994, would use Superga shoes on the catwalk. Think that then, as a consequence, since the mid-90s brands started producing their own sneakers to use in fashion shows.”

Among the Superga campaigns curated by Turcati, a series shot in both Italy and France between 1987 and 1988 stands out for its enigmatic and neoclassical feeling suspended between the ancient Greece ideal of male beauty and 1930s sportswear aesthetics.

"We decided to highlight the overall over the individual, so we never showed the models’ faces entirely. The staircase had a strong semiotic meaning too, maybe it’s because they represent the ladder of success,” jokes Turcati.

“Whilst I was travelling across Italy for work, I found myself in Ancona for a meeting with a client that produced Ferrè watches. When we left the restaurant, I had a vision about a big staircase by the Passetto hill. The following week I had to go to Rome, so I picked my son, a white outfit, a tennis racket and drove there by car. I diverted to Ancona again and we shot some test photos in colour. When a few weeks later we presented these ideas, the campaign was approved straight away.”

Inspired by English architecture and jazz tradition the Superga Springfield campaign shot in San Francisco was another landmark in Turcati’s career. Franco Turcati.

The success of those Superga campaigns, won Turcati an airplane ticket for San Francisco where he shot another campaign, this time for the brand’s US college basketball tradition-inspired Springfield hi-top sneakers. Balancing his trademark Italian style with American jazz culture, the photographer conceived another iconic campaign. “We shot mostly around Golden Park, mostly inspired by the use jazzmen made of sneakers. The saxophone was a tribute to Charlie Parker, but it was also chosen following the lesson of the great Turinese graphic Armando Testa who praised the impact of the silhouette in advertising.”

Now Turcati is retired in Turin where he has just taken part to Photo Action, an initiative to support the national health system during the Covid-19 emergency through the sale of photographs.

What can be learnt from the career of Turcati, though, is that in life nothing is truly ever set in stone because new paths of existence can continually unfold upon our eyes if we keep pushing creativity and learning forward, always by acting with a touch of charm.

All photographs by Franco Turcati for Synaesthetic Magazine. Do not re-use or share without permission. All rights reserved.